FACTORY LIFE + MEMORIES

Generations of families and communities thrived around Holden factories.

Keeping time

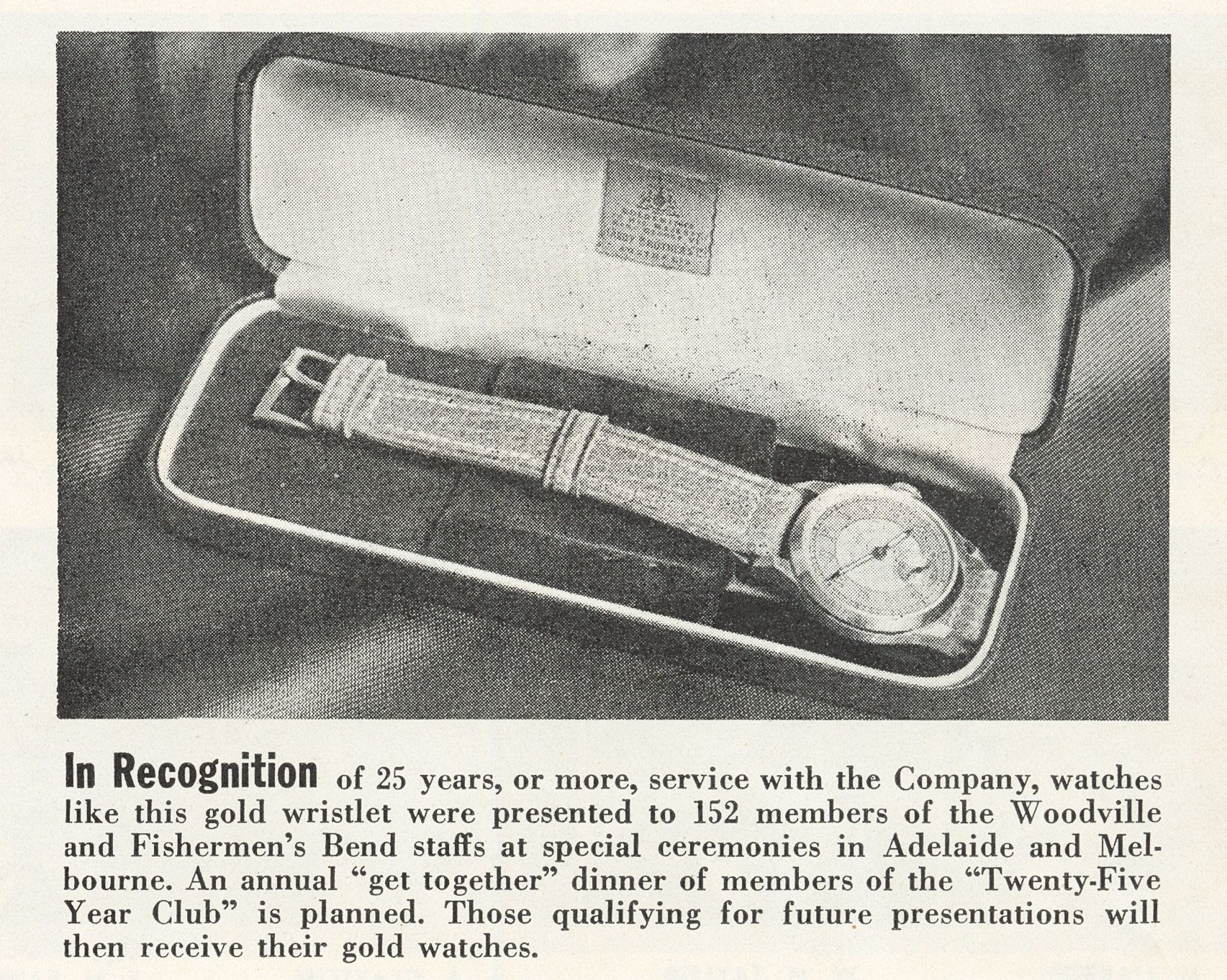

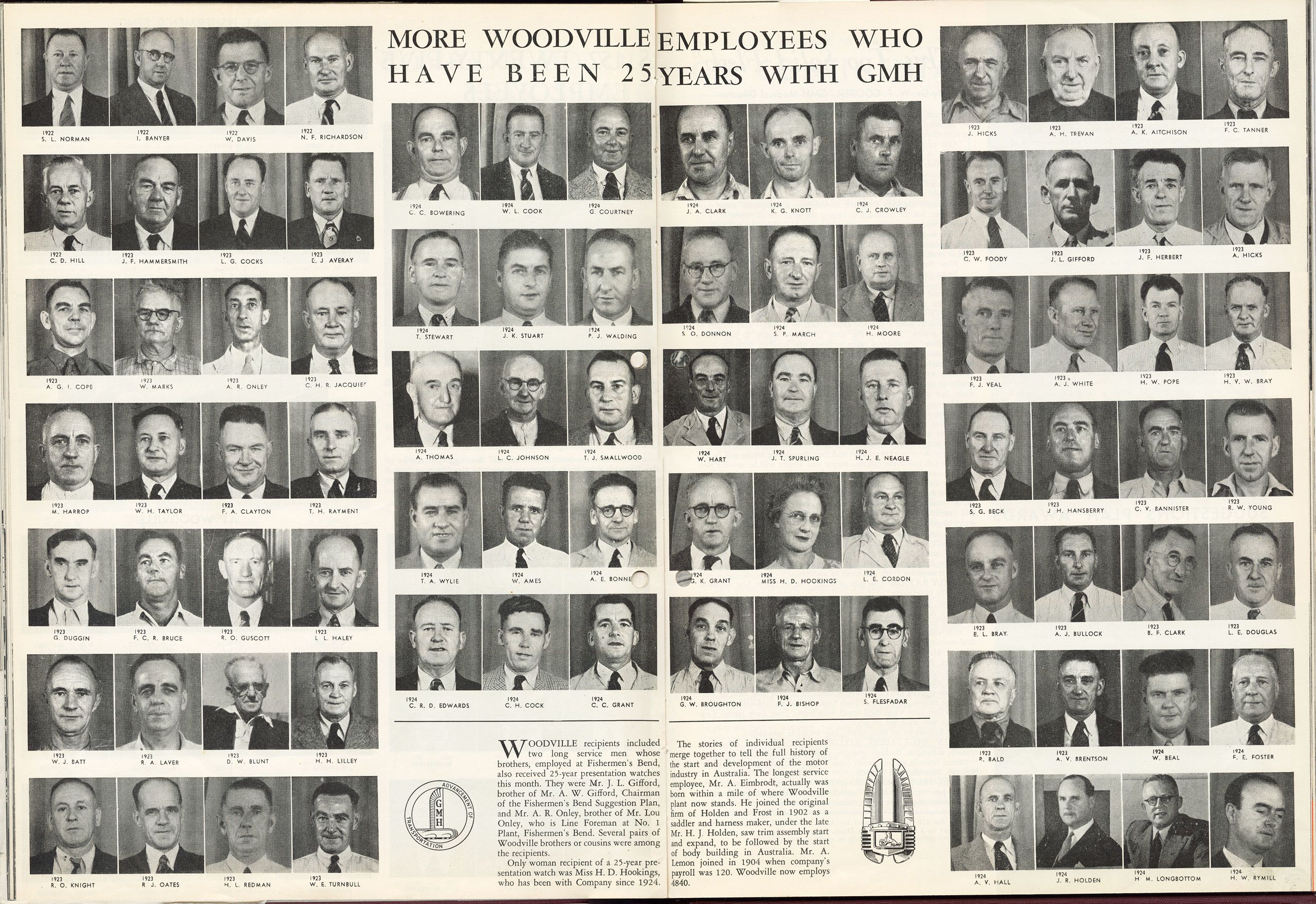

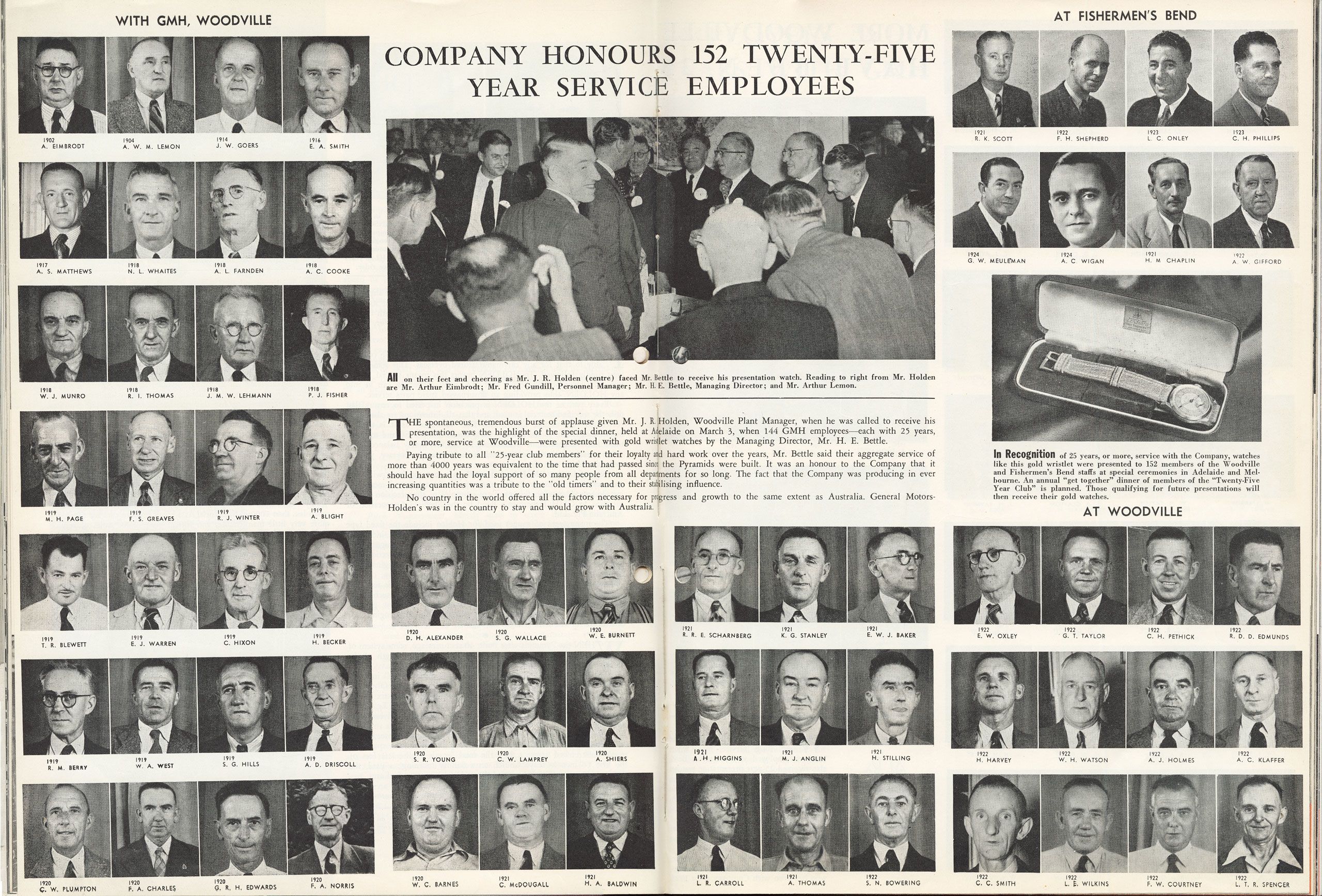

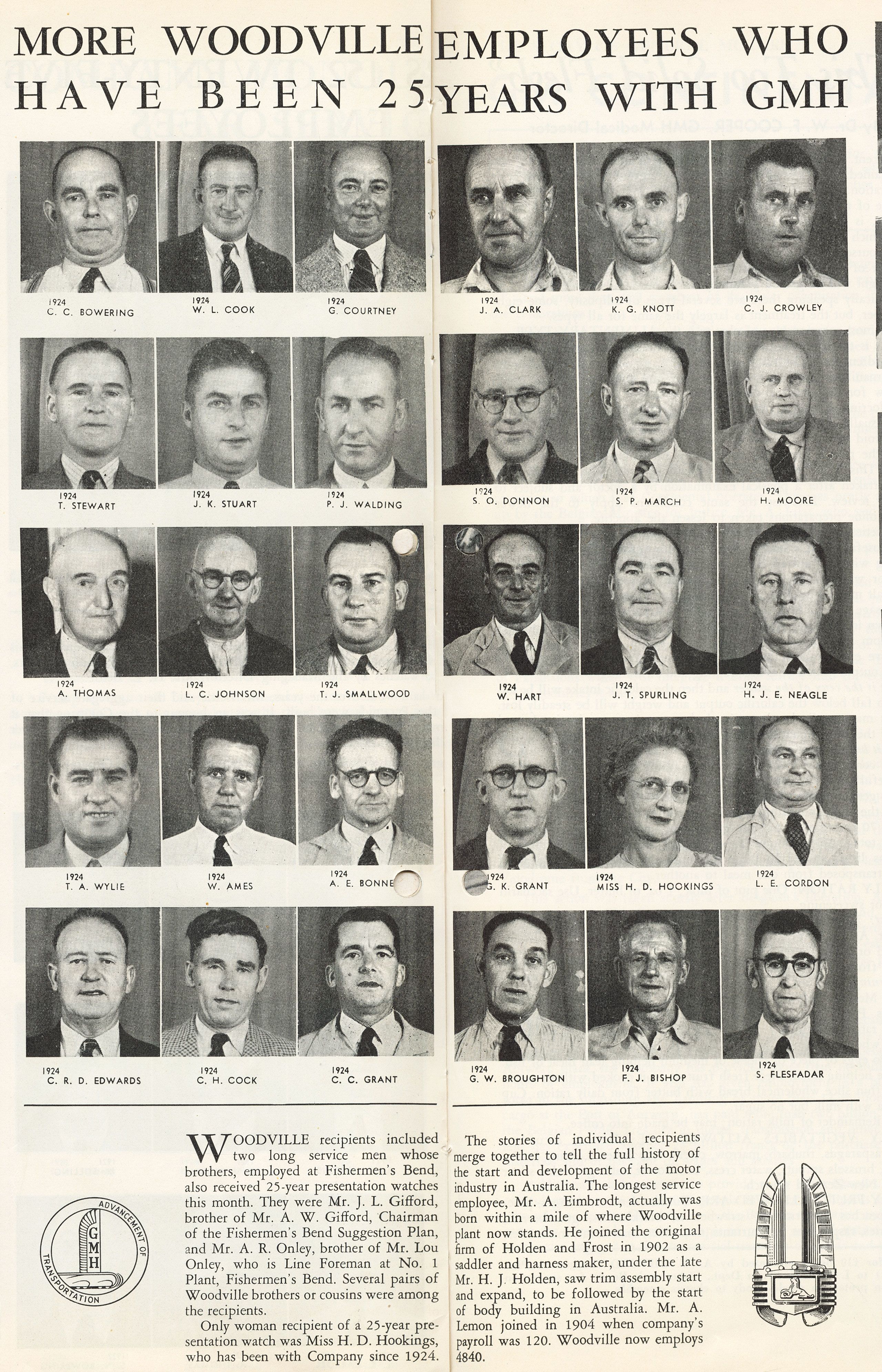

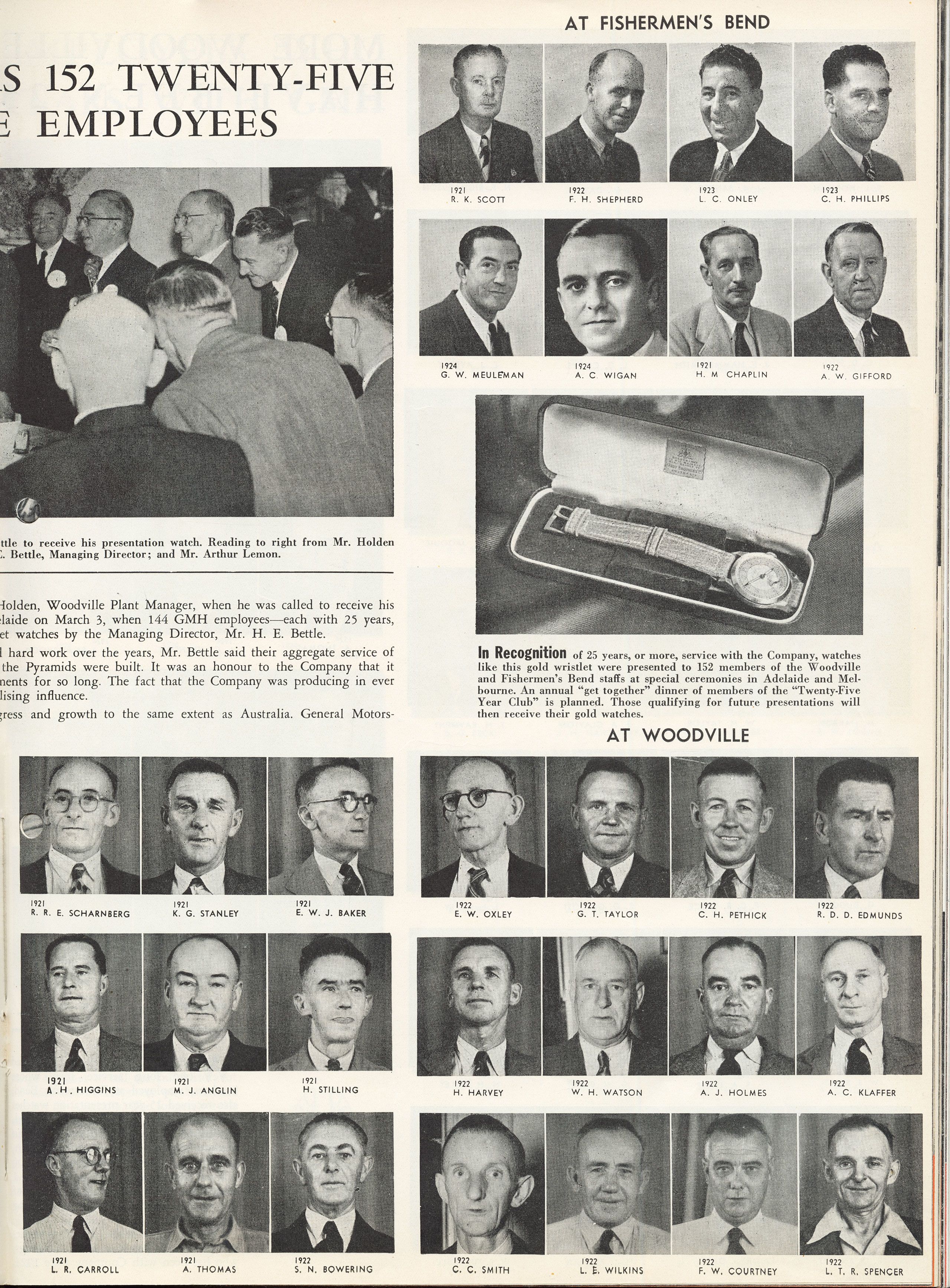

In the aftermath of World War II Australian companies competed to attract employees not just with better pay, but also with more attractive facilities and conditions such as social and sporting clubs, canteens with subsidised meals, entertainment, and reward programs. In 1949, troubled by ongoing labour issues, Holden introduced a ‘gold watch scheme’ to reward workers who gave ‘loyal and faithful service’, and the following year 152 employees became the first to be admitted to GMH’s ‘Twenty-Five Year Club’.

The same, Swiss make of watch was given to all recipients regardless of their job or position in the company, and each year presentations were made at exclusive dinners, attended by top executives and past recipients.

An image of a gold watch presented to members of the 'Twenty-Five Year Club' featured in Holden's People magazine. SLSA: BRG 213/92/03/8-9

An image of a gold watch presented to members of the 'Twenty-Five Year Club' featured in Holden's People magazine. SLSA: BRG 213/92/03/8-9

‘It was a big deal for a lot of people. It was always well-known that these blokes have got gold watches; it was something that a lot of people aimed for’.

Sometimes workers would delay retirement to reach the milestone.

At their peak the lavish annual presentations were held in five states. By 1964, there were 1545 members of the gold watch club. The Adelaide dinners were always the largest and had to be held at Centennial Hall at the showgrounds, the only place then large enough!

By the late 1970s, tougher economic conditions, and the fact that the functions had become so large, meant the company had to restrict invitations to those receiving their awards that year. This upset many, including the gold watch retirees who used to look forward to the opportunity to reconnect with their former workmates. In the early 1980s, the free meals were crapped altogether, sparking uproar that was reported in the local press.

In response to this decision disgruntled members of the GMH Woodville tool room protested by forming their own twenty-five-year club.

By the 1980s, the choice of awards had vastly expanded. Gold watches were still popular, but many opted for other items such as golf clubs, a mantel clock or video camera.

GMH watches rarely come up for sale. They are kept and passed down through generations. Former workers speak of their parents’ and grandparents’ gold watches as important milestones in their working lives. Bob Smith knew the importance placed upon the reward scheme by those who worked there. This included his father, a tool maker who retired soon after receiving his watch.

‘It’s an Omega, it’s not battery operated, you’ve still got to wind it. It still works…It’s got the engraving on the back: ‘Presented to S.F. Smith from General Motors-Holden 1946–1972’. When my father passed on, it was then given to my son, he wore it for a long time…He treasures it, and he’s a mad Holden man too.’

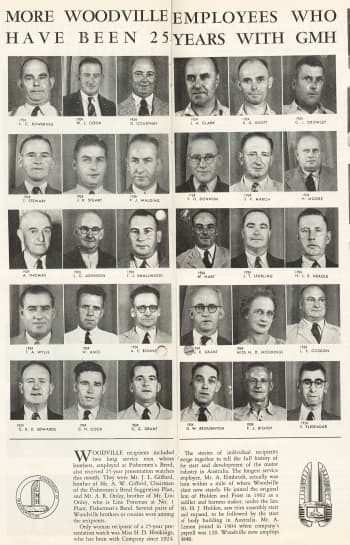

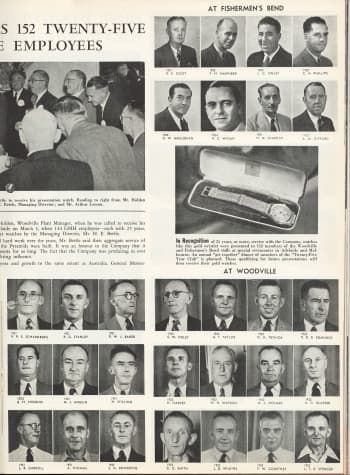

Some of the men, and one woman, inducted into the Twenty-Five Year Club. People, March, 1950

Some of the men, and one woman, inducted into the Twenty-Five Year Club. People, March, 1950

Some of the men, and one woman, inducted into the Twenty-Five Year Club. People, March, 1950

Some of the men, and one woman, inducted into the Twenty-Five Year Club. People, March, 1950

"It's like having your house knocked down"

The lament that often surrounds factory closures is for workers’ lost livelihoods. What the experience of GMH Woodville shows is that workers could also grieve the loss of community and place. While workers’ memories of their physical environment accorded, in many cases, with company records, their recollections of emotional connections and social interactions provide a different window by which to view and understand factory life.

Before starting as a 17-year-old apprentice patternmaker, schoolboy Bruce Heaft had sold newspapers to workers rushing out the gates.

‘At knock-off time you would have these thousands of people coming out, buying papers from you… it was just a body of people, just running out’.

Of his early years at Holden he recalled,

‘The size of it. It was overwhelming really…it was noisy. …It was reasonably clean in the area I was. I wasn’t in the production side. I’m in the development side. And so patternmaking, toolmaking, all of those areas, it was a necessity to keep everything tidy…But I do recall when I had to go over and work in the mill to help out there. Now a mill is where they just machine big hunks of timber down. And I could see over the Cheltenham railway line, and I could see Woody High School there. And I can remember having a tear in my eye thinking, “What have I done?” because you’ve got machinery working at such a high revs per second, and it shrieks, everything is shrieking. I actually did lose a bit of my hearing…’

However as he became more experienced and completed his apprenticeship he explained

‘…as we went on and on at Holden’s, it became like another family and you’re all very close. It was a way of life, and it was a way of life that was very good in that it supplied you good money. It supplied you with friendships. It supplied you with security. So to me, it was an ideal place really to work.’

Bruce worked at Holden for 43 years. Post retirement, when travelling along Port Road past the old Holden site, now home to a hardware store, he would remember.

I think I used to play cricket out here at lunchtimes or sleep up on the roof in the sun… Woodville was like a home to me and it’s like having your home knocked down.’

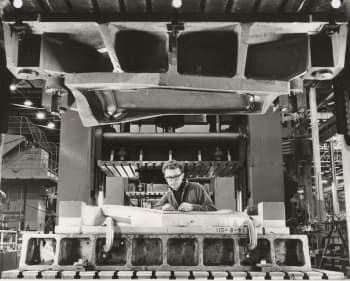

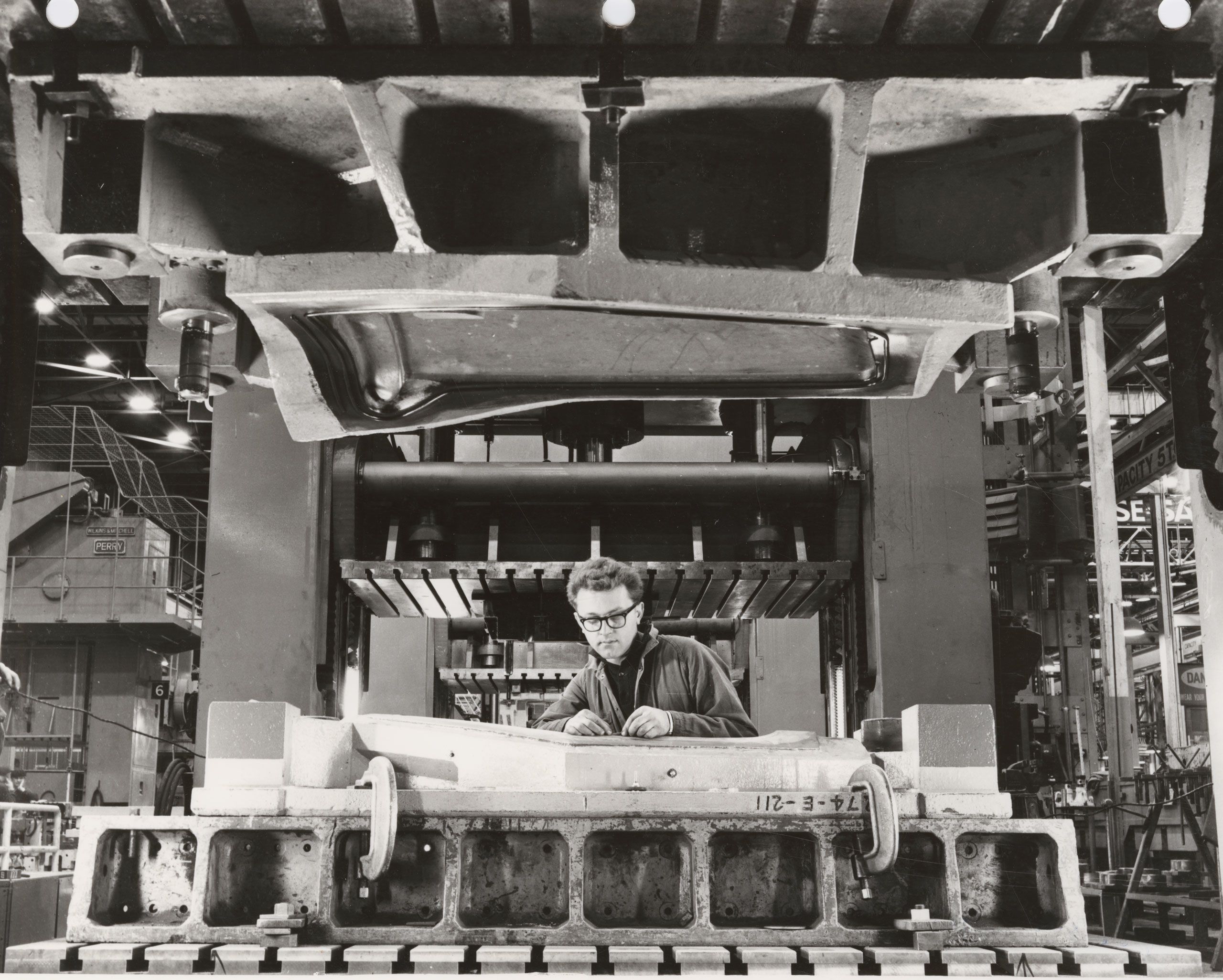

Woodville toolroom, c1973. SLSA: BRG 213/77/54/7

Woodville toolroom, c1973. SLSA: BRG 213/77/54/7

Apprentices, 1945. SLSA: BRG 213/207/1/856

Apprentices, 1945. SLSA: BRG 213/207/1/856

Knock-off time, 1941. SLSA: BRG 213/207/5/397

Knock-off time, 1941. SLSA: BRG 213/207/5/397

‘When the five o’clock whistle blows’, 1929. Shows employees going to catch trains at Holden’s private railway station that adjoined the Woodville plant. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 397/7/366

‘When the five o’clock whistle blows’, 1929. Shows employees going to catch trains at Holden’s private railway station that adjoined the Woodville plant. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 397/7/366

The Woodville Whistle

Many employees at Woodville were born and raised in the western suburbs of Adelaide, so their first memories were often from outside, not inside, the company gates. The factory’s steam whistle signalled the start and finish of each shift. It was heard by generations of residents living within five or six kilometres of the plant.

In 2019 Stephen Hack recalled his father Bob, a 38-year Holden veteran, running a tight schedule at home. He required his children to be at the dinner table at 5 o’clock sharp.

‘If you weren’t home on time, by crikey, you’d get in strife, yeah, you had to be home on time’.

After working at Woodville himself, Stephen understood why his father insisted on such a regimented homelife.

‘Holden’s does that to you. You start work at 7.30. There’s a 7.28 whistle where you should be at your workstation, changed, ready to go. Whistle goes, 7.30 start work. Morning tea was at whatever time it was, you’d have a whistle … Right through … 4.08 the whistle would go, knock off. And if you got to work late, you were docked for every six minutes.’

Anthony Vassallo spent four decades working at Woodville, his days regulated by the steam whistle that heralded the start and end of each shift. It was the place where he learned the ways and slang of his adopted country, earning promotion and a decent wage to support his family. But then his working life was cut short by an industrial accident that crushed his leg. After years of pain, and multiple operations, Anthony died aged 72, but he never lost his connection to his former workplace.

His son George, who followed his father and grandfather into Woodville, recalled his dad’s fierce pride in having worked for Holden.

‘My father loved his job … his wishes were that if he was to pass away that he be buried in the Cheltenham Cemetery, which was opposite Holden’s, and that he’d be facing the plant. He wanted to hear the whistle every day. So, that’s what we did.’

‘Something attempted, something done’ The Bulletin, 21 November 1934

‘Something attempted, something done’ The Bulletin, 21 November 1934

‘Holden’s whistle’ The News, 26 February 1926.

‘Holden’s whistle’ The News, 26 February 1926.

‘A false alarm’ The Register, 4 September 1929

‘A false alarm’ The Register, 4 September 1929

‘Wally’s final whistle’ People, April 1989

‘Wally’s final whistle’ People, April 1989

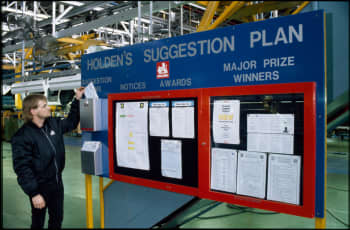

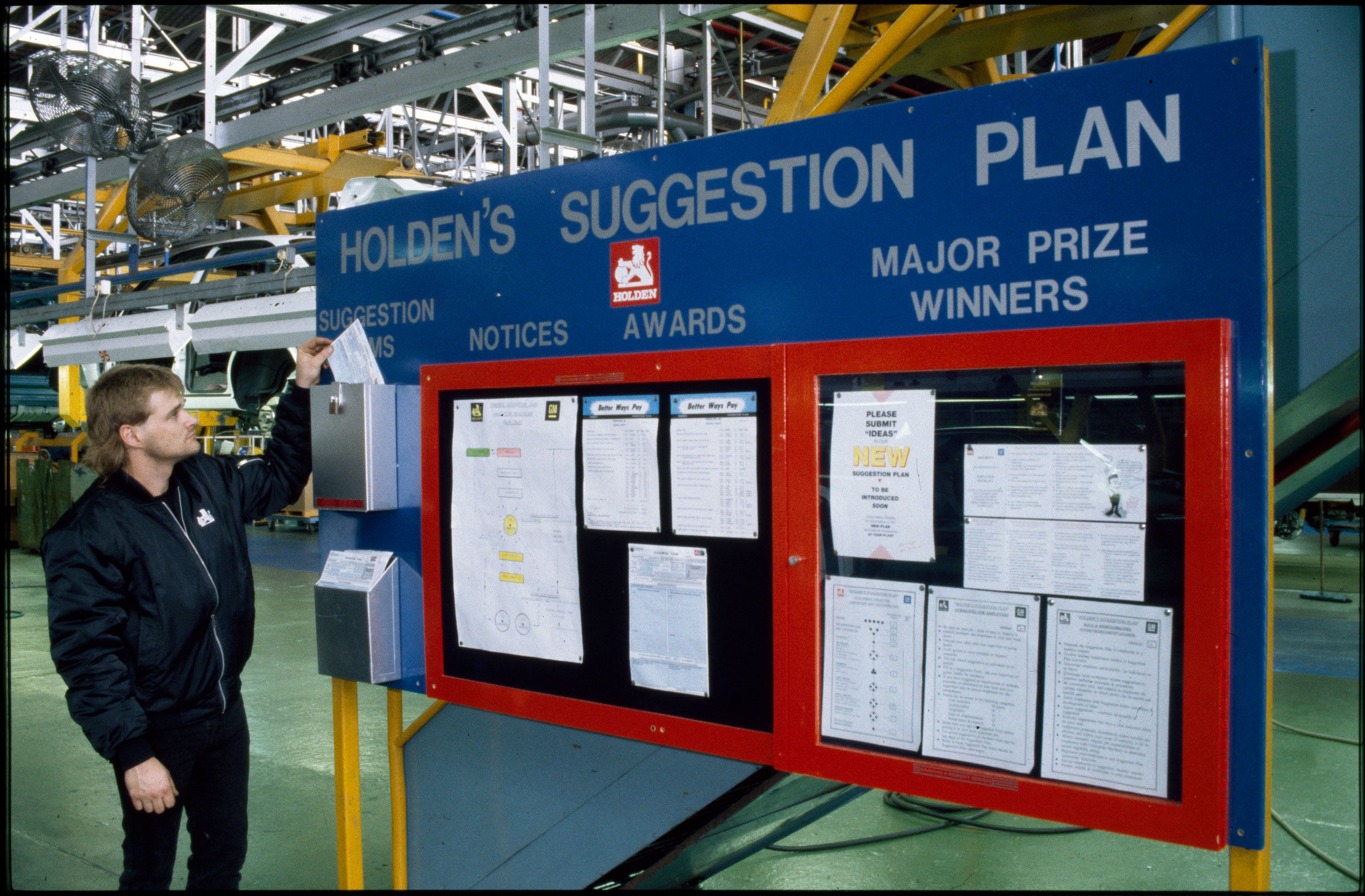

Suggestion scheme

The GMH suggestion scheme began in 1931. Workers were financially rewarded for ideas that benefitted production, design, administration, and worker safety.

The amounts awarded varied but could be quite substantial. Peter Williamson was awarded the maximum, $25,000 in 1989, for his idea to recycle plastic seat covers. This provided annual cost savings of $79,000. The previous month Nazzareno Bagnato, leading hand at the Elizabeth Stamping section, received the same amount for his idea to use blanking steel off-cuts to construct support dashboard panels. This saved the company $149,000 per year.

Tony Leggatt was a toolmaker at Elizabeth and a member of the ‘Twenty-Five Year Club’. He remembered working on suggestions with his workmates:

‘We put in suggestions as a group. A good suggestion I got, I think it was $6,000 for, was changing incandescent light globes to compact fluoros in the tunnels. Because in the tunnels it was hot and they never lasted that long, the incandescent fluoros. But compact fluoros lasted a lot longer. And in a tunnel you needed an electrician, two electricians to change the light globe, plus one safety person. So it was three people to change a light globe.’

$25,000! What a great idea!, People, October 1989. SLSA: BRG 213/92/35/2/2

$25,000! What a great idea!, People, October 1989. SLSA: BRG 213/92/35/2/2

Two awards at Woodville, People, December 1954. SLSA: BRG 213/92/7/3/13

Two awards at Woodville, People, December 1954. SLSA: BRG 213/92/7/3/13

‘Basil’s business is booming’, People, December 1979. SLSA: BRG/213/92/26/1/6

‘Basil’s business is booming’, People, December 1979. SLSA: BRG/213/92/26/1/6

‘Peter uncovers $25,000 award’, People, December 1989. SLSA: BRG 213/92/36/3/2

‘Peter uncovers $25,000 award’, People, December 1989. SLSA: BRG 213/92/36/3/2

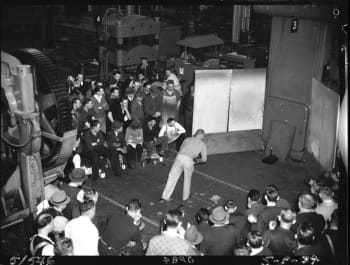

From quoits to Christmas

Workers’ memories of Holden frequently refer to the social life and the sense of community commonly referred to as ‘the Holden family’. Employees were encouraged to maintain their links to the workplace during their off-duty hours through social activities and sporting clubs associated with the company.

During the Second World War concerts were held in the factory grounds, and there were wrestling and boxing matches.

In the 1950s the wide Port Road median strip was leased from the local council to provide a car park and recreation grounds. These included several bowling greens, an arena for electric light cricket and courts for tennis, netball and basketball.

The September 1964 issue of People magazine reported that Woodville’s ‘vigorous’ Sports and Social Club had 60 affiliated clubs including debating and camera clubs, golf, carpet bowls, darts and quoits.

Annual picnics were held in places such as Belair National Park or the Barossa Valley. Held on Sundays, the slowest day production-wise, the picnics featured events such as egg and spoon races, as well as more high-level running races and of course the tug of war.

The Christmas parties at Elizabeth were huge affairs and were the envy of non-Holden employees. Father Christmas would arrive by helicopter or on the tray of the latest model ute, with a present for each child of employees.

These clubs and events could give workers from all sectors of the organisation, and their families, a sense of identity and belonging. Not all people took part in the social activities, viewing work as ‘just a job’, but for many they remain an enduring memory.

Lunchtime quoits at Woodville, 1943. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 213/207/5/546

Lunchtime quoits at Woodville, 1943. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 213/207/5/546

GMH Bowling Club, Port Road, Woodville, c1961. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/720

GMH Bowling Club, Port Road, Woodville, c1961. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/720

Picnics at Elizabeth and Woodville, People, May 1978. SLSA: BRG 213/92/25/2/7

Picnics at Elizabeth and Woodville, People, May 1978. SLSA: BRG 213/92/25/2/7

Christmas at Elizabeth, People, December 1988. SLSA: BRG 213/92/35/4/10

Christmas at Elizabeth, People, December 1988. SLSA: BRG 213/92/35/4/10

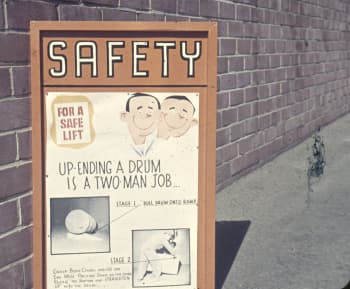

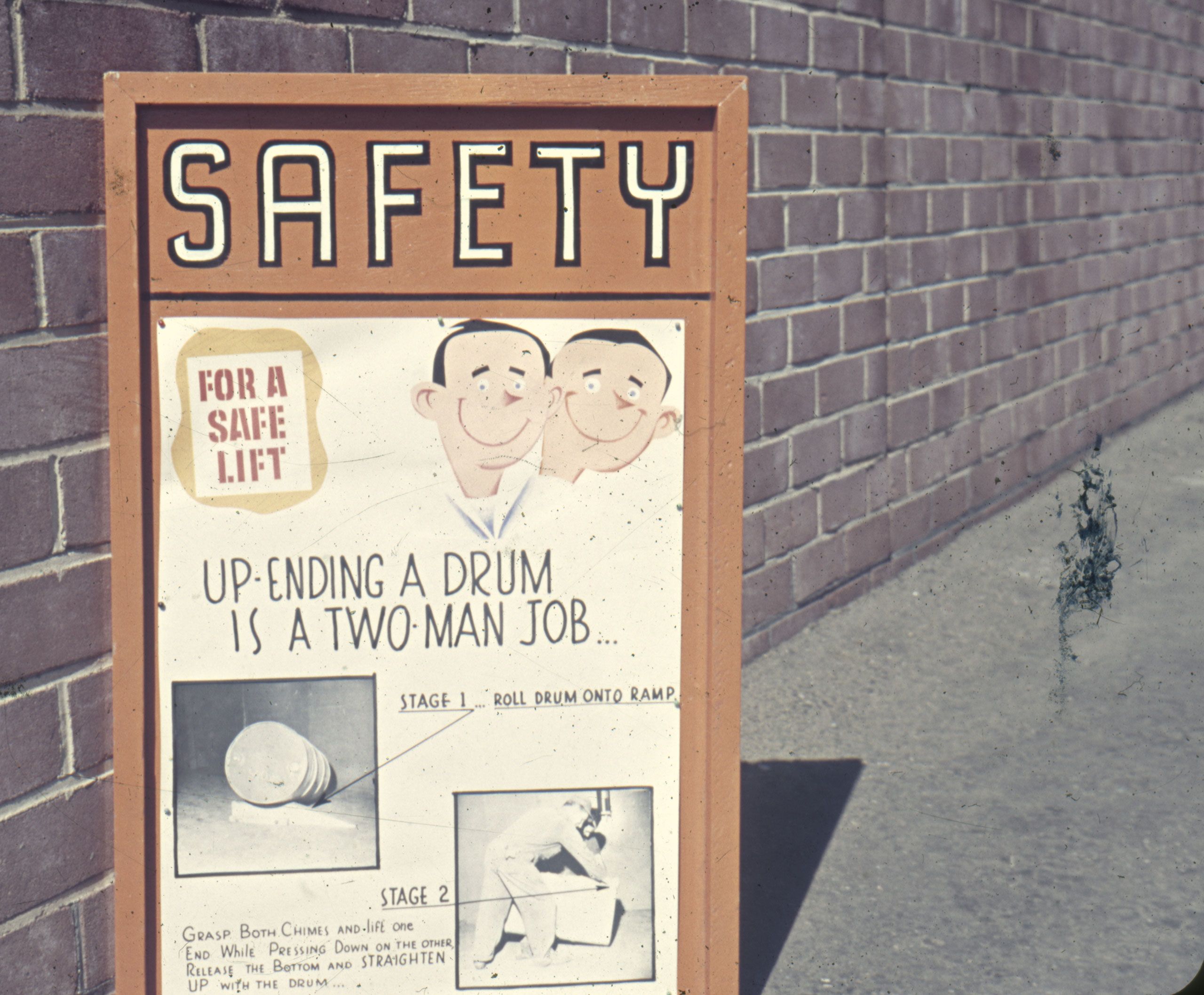

Protecting the workforce

GMH’s annual reports and in-house magazines consistently declared its commitment to a safe working environment. There were safety engineers and modern medical centres, staffed by full-time doctors and nurses, at each of its factories.

Sarah Barr was an occupational nurse at the Elizabeth from 1973 to 1985. She recalled the medical centre having an X-ray machine, rehabilitation centre, hearing department and visiting physiotherapists. She estimated that the centre treated about 300 patients a month.

Safety sign at Woodville, c1960. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/453

Safety sign at Woodville, c1960. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/453

Despite the company’s and employees’ commitment to safety, in such a dangerous workplace, accidents did happen. Sometimes they were considered minor, sometimes they were far more severe.

‘There was one person, put his hand on the top of the die. And when they pressed the pins, it pushed the die straight up and he squashed all his fingers, his fingers were ruined for life, so that was a terrible situation, you know. … that was very horrific.’

Analysis of hand injuries at Woodville and Elizabeth, 1961. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/759

Analysis of hand injuries at Woodville and Elizabeth, 1961. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/759

Many workers considered injuries an inherent risk of the job or the result of inattention. Eye injuries were common. They usually involved metallic dust or tiny shards of metal where metal was being worked. For much of the company’s history safety glasses and hearing protection were optional. As the years progressed the company would take a far stricter line on the use of such equipment.

But sometimes protection was provided only when the worker demanded it.

Judith Daenke started at Elizabeth in 1973 as a sewing machinist in trim fabrication. She recalled that the ‘trim fab girls’ all came into work ‘looking quite nice with their make-up and hair done’. During slow periods some of them would be deployed to other areas of the factory.

‘They actually put me on this welding machine, which was probably about 10-foot-high, but probably only about a metre wide, and you had to put a piece of metal in to, for it to join this other piece and if it didn’t strike square, then sparks flew out everywhere. And that’s pretty intimidating. I had a Crimplene dress on, quite a pretty dress, navy blue pleats and white at the top and red trim and stockings of course. Well there I am, sitting at this press with it spitting at me. So, I just went, ‘No. Stop’. So finally, the supervisor came and I said, ‘Look, I need a leather apron and some leather gloves or something. I’m getting burnt. I’m not doing this until I get some safety equipment’. So finally, he brought me back a leather apron and leather gloves.’

‘Medical centre gets a facelift’, People, March 1986. SLSA: BRG 213/92/33/1/8

Casualty room at Woodville, 1945. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 213/207/1/90

Casualty room at Woodville, 1945. Photographer D Darian Smith. SLSA: BRG 213/207/1/90

‘Protective lens saves John’s eye’, People, June 1977. SLSA: BRG 213/92/24/3/12

‘Protective lens saves John’s eye’, People, June 1977. SLSA: BRG 213/92/24/3/12

‘Medical centre gets a facelift’, People, March 1986. SLSA: BRG 213/92/33/1/8

‘Medical centre gets a facelift’, People, March 1986. SLSA: BRG 213/92/33/1/8

A new start

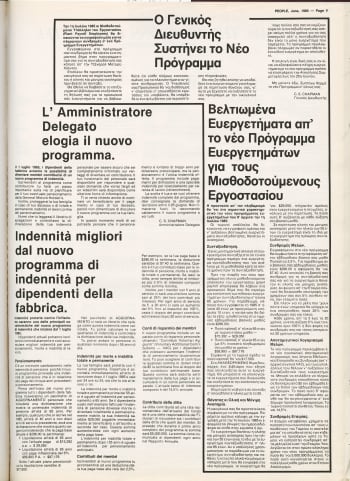

After the Second World War through to the 1970s and the 2000s, Holden became a melting pot of cultures as new waves of migrants came to Australia. The workplace could provide more than a weekly wage. It could provide training, community and stability in a new country. It could also provide a window into their Australian workmates’ ways and language.

Woodville pay office, with English, German, Italian and Greek languages on the sign, c1964. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/723

Woodville pay office, with English, German, Italian and Greek languages on the sign, c1964. SLSA: BRG 213/77/84/723

For recently arrived migrants seeking to learn or improve their English language skills, Holden provided a means. As workers greeted their workmates at the start of the shift, took a smoko, mingled over lunch or lunchtime games, and spoke with their supervisors, they picked up and practised basic English phrases and learned Australian idioms and ways of communication.

English language classes were offered at both Woodville and Elizabeth - in one of the quieter parts of the factories.

Tony Pitrakkou arrived in Adelaide from Cyprus in 1948. Except for a period when he was employed at Chrysler, he worked at Holden until 1981. He was interviewed at 93 years of age and recalled the day after he arrived in Adelaide when his cousin, who already worked at Woodville, took him to the plant.

“They say, ‘Give him a job’. I don’t know anything about the factory. I’ve never been in factory. And I say, ‘Now, my God, how, how I can know that different job?’ And everybody say to me, ‘Don’t worry. When we come here, we didn’t know anything about the job. But they show us. They stay about two, three minutes with you. They show you. And finish’.”

Duncan Hockley started as an apprentice electrician in 1958.

“The main impressions I got from the early years of my apprenticeship came from the vast and various experiences of the non-Australian tradesmen and what had happened to them in the Second World War and when they came to Australia. They covered a wide range of European backgrounds… What I got from all this was a wide education in contemporary European history by people who had lived through it and escaped. What I also remember from working with them was that there seemed to be little or no animosities amongst them as a result of their previous life experiences. There seemed to be an attitude of a new start in a new country.”

English language class at Elizabeth, c1993. SLSA: BRG 213/179/9/1/37

English language class at Elizabeth, c1993. SLSA: BRG 213/179/9/1/37

Leo Corrieri was a third generation Holden employee. His father’s English became fluent as he became a foreman but, when Leo fondly remembered his grandfather.

“He worked at Holdens, he was only there for four years, spoke no English whatsoever even until the day he died, God bless his soul, he learnt about four words, five words and they weren’t nice words.”

The son of Vietnamese refugees, Martin Nguyen began at Elizabeth in 2004 and remained there until the final months of the factory’s operation in 2017. His father worked at the Mitsubishi factory at Tonsley Park and his mother got a job at Holden. She also finished in 2017 when Elizabeth closed.

‘Being from an Asian family, I was expected to become a doctor because there was high expectation from immigrants but I’m grateful that I went to Holden because it sort of led me to the right direction. I learnt the value of hard work and more importantly, study—which I did while I was working at Holden. Holden were very specific about bullying. As in diversity being a young Asian worker. There is reporting tools if you’re racially victimised and you can always say that that sort of behaviour was not on. And I’m glad that the workers weren’t like that because half the workers there were immigrants as well. So it was not on. There were some cases where I’ve seen bullying but they were quickly squashed by management because we did have a diversity policy. Which I’m glad they did and generally speaking all the guys down there were very accepting.’

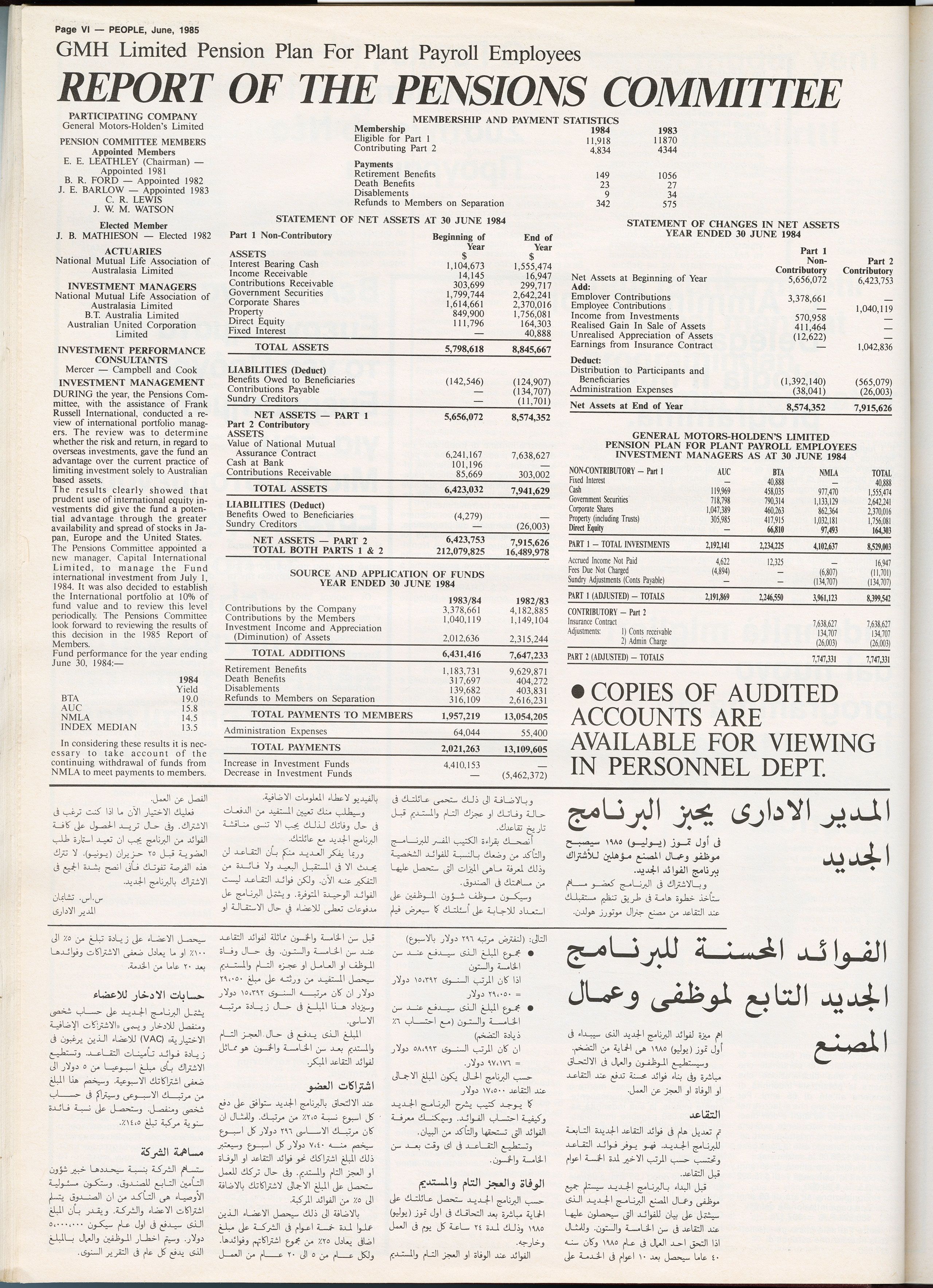

Articles in Italian, Greek, Vietnamese and Turkish in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2

Articles in Italian, Greek, Vietnamese and Turkish in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2

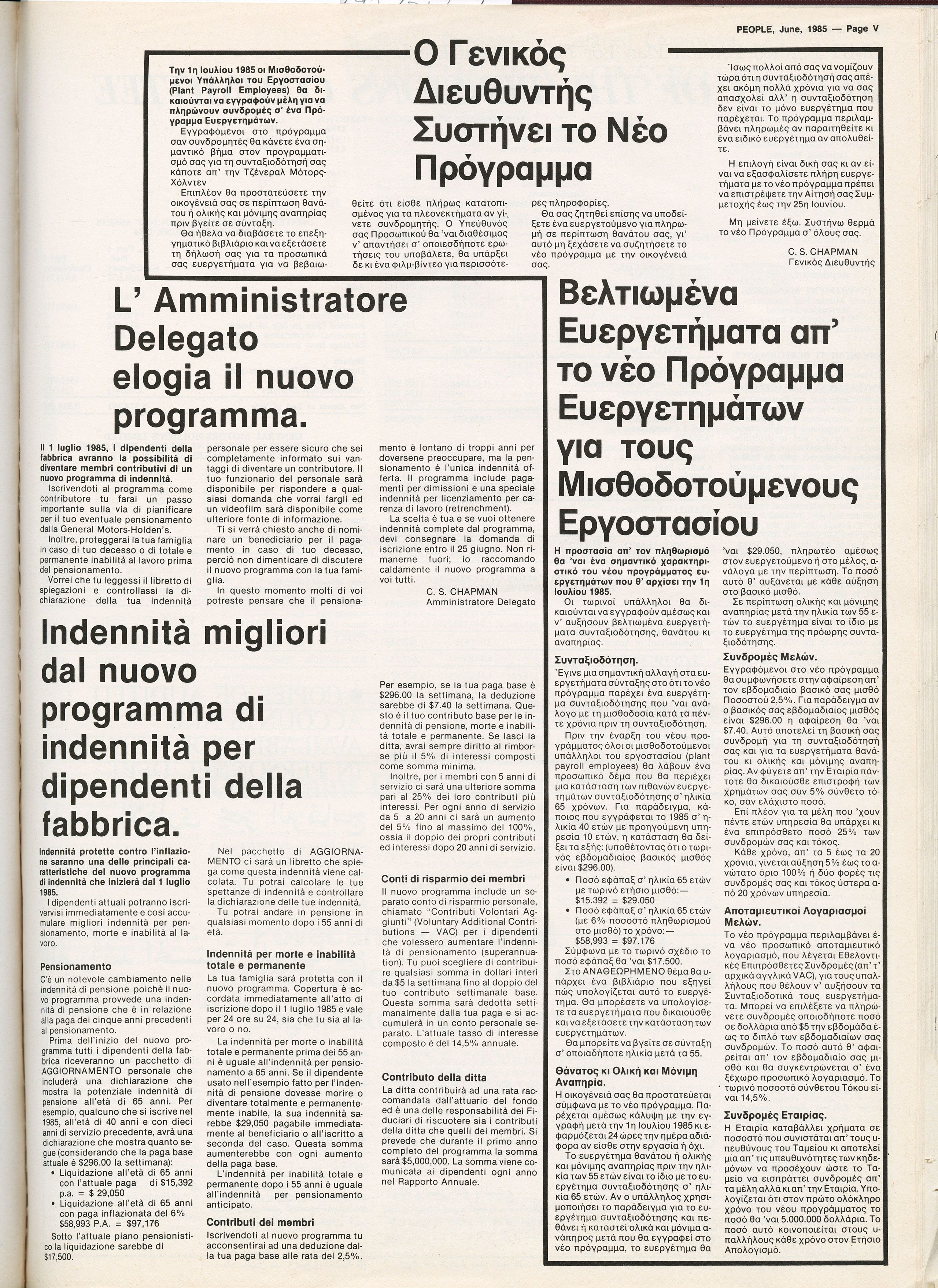

Articles in Italian and Greek in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2

Articles in Italian and Greek in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2

Articles in Turkish in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2

Articles in Turkish in People June 1985. SLSA: BRG 213/92/32/2